Considering Uncertainty

Read the special issue editor Djoeke van Netten’s introduction “Introduction. Mapping Uncertain Knowledge” here.

Djoeke van Netten

University of Amsterdam

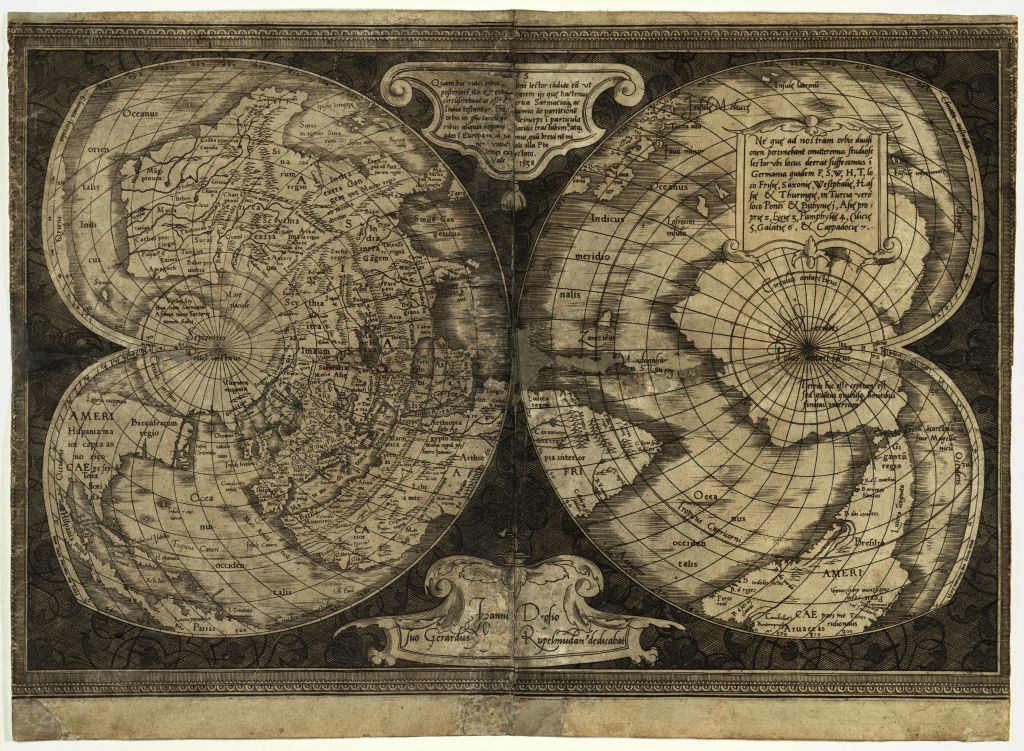

Like many other things we’re still dealing and grappling with as historians – capitalism, globalization, colonialism, nation building, and modern science – many of the visual-epistemological conventions of cartography emerged in the early modern period. America and Australia were added to our vision of the ‘old’ world, the Mercator projection was born, the north moved to the top of the page, and the new genre of the Atlas became popular on the early modern book market.

Maps both represent and shape knowledge, they simultaneously demonstrate the scope of accumulated knowledge and intervene in how we view the world. In particular, maps lay at the intersection of scholarly geographic and cartographic work, imperial, political imaginations of space, and indigenous knowledge and encounters and thus productively open up narrower conceptions of science. And yet, the history of knowledge and the history of cartography are largely unaware of each other. Our special issue shows what both can learn from each other.

If cartography is an act of mapping knowledge, how do cartographers deal with uncertainty? What did mapmakers do when they were uncertain? How do you represent what is not known for sure? These were the questions we began thinking about in 2019. As I explain in the introduction, we discussed the Flemish map-maker Gerardus Mercator’s (1512–1594) approach to uncertainty. On one of his earliest maps, printed in 1538, he wrote of uncertain knowledge as that which is known to exist while its exact place, limits or details were yet to be established. Uncertainty, then, lays somewhere in the grey zone between complete certainty and complete ignorance and is at once more interesting than either. Consider the temporal index of Mercator’s definition: yet to be established. Uncertainty, then, is where knowledge advances and history is made, with all of the violence that that entails.

This special issue – braving many of its own uncertainties from conference applications, rejections, and acceptances, global pandemics, firings, hirings, burn-outs and even, sadly, one death – is finally out. It hopes to illuminate some uncertainties and productively create new ones for future historians to uncover.

World map by Gerhard Mercator, 1538. Public domain, Wikimedia.

You must be logged in to post a comment.