“Those Curious Repositories of the Sentiments and Actions of Men”

Read André de Melo Araújo’s research article “(Re)producing the English Printed Past. Antiquarian Knowledge-Making Practices in Joseph Ames’s Typographical Antiquities (1749)” here.

André de Melo Araújo

Universidade de Brasília

In October 2016, I visited the Museum Plantin-Moretus and the Hendrik Conscience Heritage Library in Antwerp to look for early modern printed and handwritten works on the art of printing. It was right next door to Christophe Plantin’s own flourishing sixteenth-century printing shop where I had the pleasure of viewing Philip Luckombe’s (1730–1803) The History and Art of Printing, published in 1771.

In its time, Luckombe’s introduction to the art of printing was marketed as the most intelligible and complete of any other title available and contained a wide variety of instructions and examples that could not be found elsewhere. However, not all of the information contained in these pages was actually new. Firstly, the text associated with Luckombe’s name had, in fact, circulated the previous year under a different title and without an author. Furthermore, this 1770 volume had been presented by the same printers and booksellers as a compilation of already-known records on the art of printing. Who, then, had written these original pages?

My interest was piqued even more when I came across the unknown author’s unconventional definition of books as “curious repositories of the sentiments and actions of men”. Over the next couple of weeks, that phrase never left my thoughts until I was finally able to track it down: Luckombe’s definition actually came from a book by Joseph Ames (1687–1759) on the beginning of printing in England. The words that stuck in my mind were, therefore, not Luckombe’s but rather Ames’.

But who was this Joseph Ames? In 1749, Ames published a work that aimed to show “the rise, progress, and gradual improvements of” the art of printing in England. To achieve this, he wrote biographical notes on various printers, some shorter, some longer, followed by their main achievements, or what he called “performances”. But what I was most interested in were the “performances” of Ames himself. How did he go about drafting, designing, and producing the book that would later be read and sourced by Luckombe?

This is what I traced in my article “(Re)producing the English Printed Past: Antiquarian Knowledge-Making Practices in Joseph Ames’s Typographical Antiquities (1749)“. Through various printed and handwritten sources preserved at the Museum Plantin-Moretus and at the British Library, I wanted to uncover how early modern scholars made knowledge about the past.

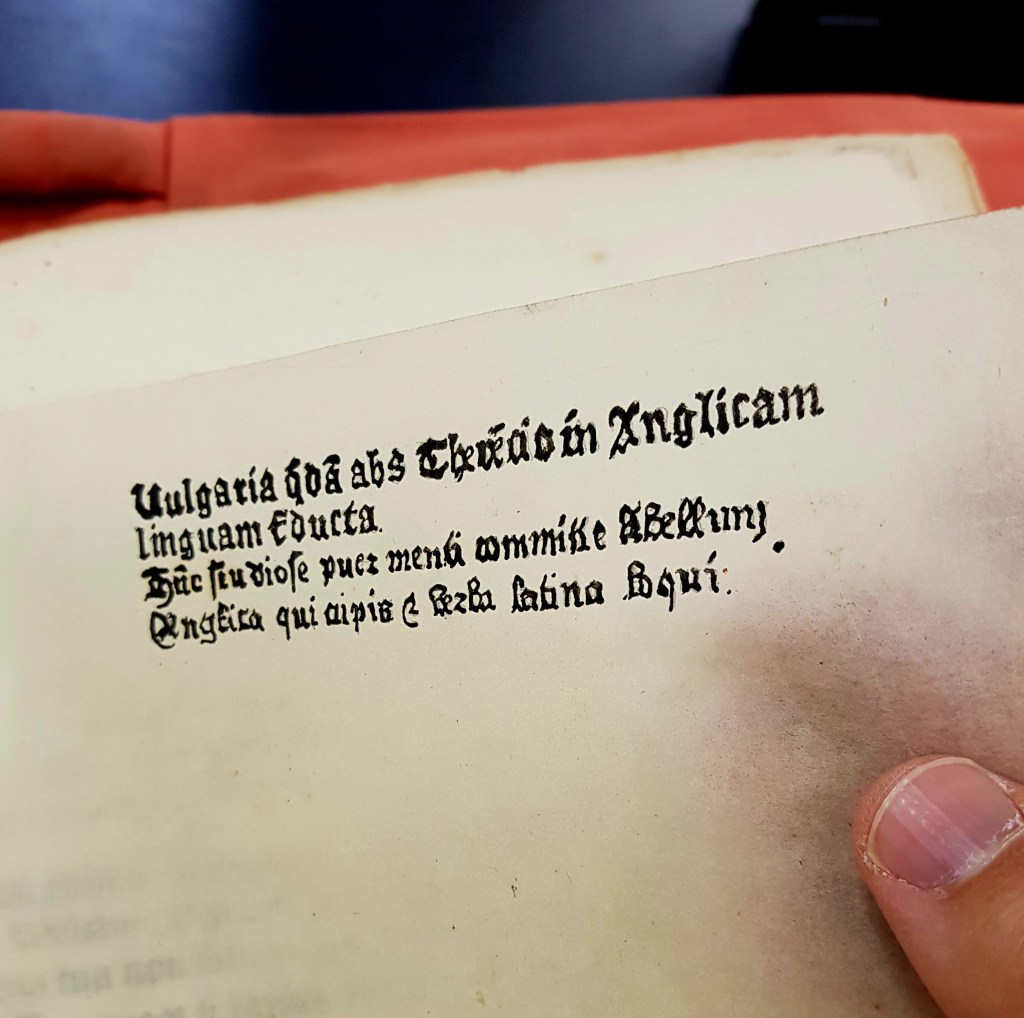

As a first step, I followed Ames’ working notes to show how this eighteenth-century antiquarian had developed a laborious system for managing bibliographical data, which he had either picked up second-hand or observed himself. Then, I explored Ames’ own collection of fifteenth and sixteenth-century printed pages and initial letters. Through this, I was able to appreciate how he went about this novel object of knowledge – the study and classification of types. However, my work in tracing the antiquarian practices of Ames and his colleagues also showed that these practices were collective endeavours and not restricted to Ames himself.

In fact, many others left detailed testimonies about how they gathered information about the first products of the English presses. While in pursuit of Ames, for example, I found out that the Cambridge University Library still preserves Mark Cephas Tutet’s (c. 1733–1785) interleaved copy of Ames’s Typographical Antiquities. Tutet was a renowned book collector and member of the Society of Antiquaries of London, where Ames was engaged as a secretary. For example, Tutet’s archives show that he – like Ames – engaged with the practice of tracing over originals as a way to (re)produce and preserve information about the past.

Just like Mark Cephas Tutet and Joseph Ames, many of their contemporaries also left handwritten, printed, and drawn testimonies of their historical working methods. These testimonies, as I argue in my paper, show the empirical perspective through which eighteenth-century antiquarians sought to engage with the material remains of the past. Viewed in this way, we are better able to understand the knowledge-making practices behind Joseph Ames’ own ‘curious repository of the sentiments and actions of men’.

Ames, Joseph. Typographical Antiquities: Being an Historical Account of Printing in England. London: W. Faden, 1749, copy: Cambridge University Library, Shelfmark: Adv.b.70.15-16.

You must be logged in to post a comment.