Why We Should Take Errors Seriously in the Age of AI

Read Alexander Campolo’s research article “Loss: A Notion of Error in Machine Learning” here.

Alexander Campolo

Durham University

Making error the central theme in a journal dedicated to the history of knowledge is admittedly a provocative choice. But this is precisely what I chose to do in my recent JHoK article.

My article not only attempts to offer another chapter in the vast history of knowledge—one I believe is significant given contemporary interest in AI—but also foregrounds the concept of error as a means to subject the category of knowledge itself to scrutiny. In other words, it asks philosophical questions about the nature of knowledge—by contrasting it with error.

The Gulf Stream by Winslow Homer (1899). The etymology of Modern English “error” can be traced back to Latin, where the term refers to “wandering” and is often related to being lost at sea—a longstanding theme in Western art. Image: The Metropolitan Museum of Art 06.1234 (public domain).

This interest in error originally arose out of a puzzle. In the historical sources that I was investigating—from statistics and computer science—discussions of error were everywhere, but it was mainly treated as an engineering problem, a quantity to be minimized. Likewise, in philosophy, error was something to be avoided, often through the power of valid deductive arguments.

But there are a few exceptions to this general rule—philosophers who treat error as seriously as reason or truth. Like many, I have been struck by Michel Foucault’s enigmatic references to “error” in his preface to the English-language edition of Georges Canguilhem’s The Normal and the Pathological.1 In it, Foucault presents Canguilhem as something of a cipher—a key to understanding not only the history of science in France but even twentieth-century philosophy as a whole.

Canguilhem chose to turn away from “noble” and mathematized sciences like physics and astronomy, toward the murkier areas of biology and medicine, where science intermingles with an individual’s experience of health and illness. These life sciences, in turn, led Canguilhem to “the problem of error,” which seems to be coextensive with life itself, especially in light of genetics and evolution. Stretching this insight to its limit, the association of error and life might offer a way out of the impasses of post-Kantian philosophy, “since,” as Foucault puts it, “knowledge, rather than opening itself up to the truth of the world, is rooted in the ‘errors’ of life.”

All of this might seem remote from the two cases studied in my article, which compares a statistical sense of error that emerges principally from astronomy in the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries, and a computational sense of error native to the twentieth century. This comparison has many important details, but one simple way of understanding it is that error became pluralized.

In the first period, astronomers and mathematicians sought to derive some sort of scientific or even metaphysical law governing “error”—in the singular—that could be used to determine the most probable estimate of some value. This proved to be untenable. Scientists working in areas like psychophysics, demography, and biometrics found that not all errors conformed to the normal distribution that had been derived in astronomy.

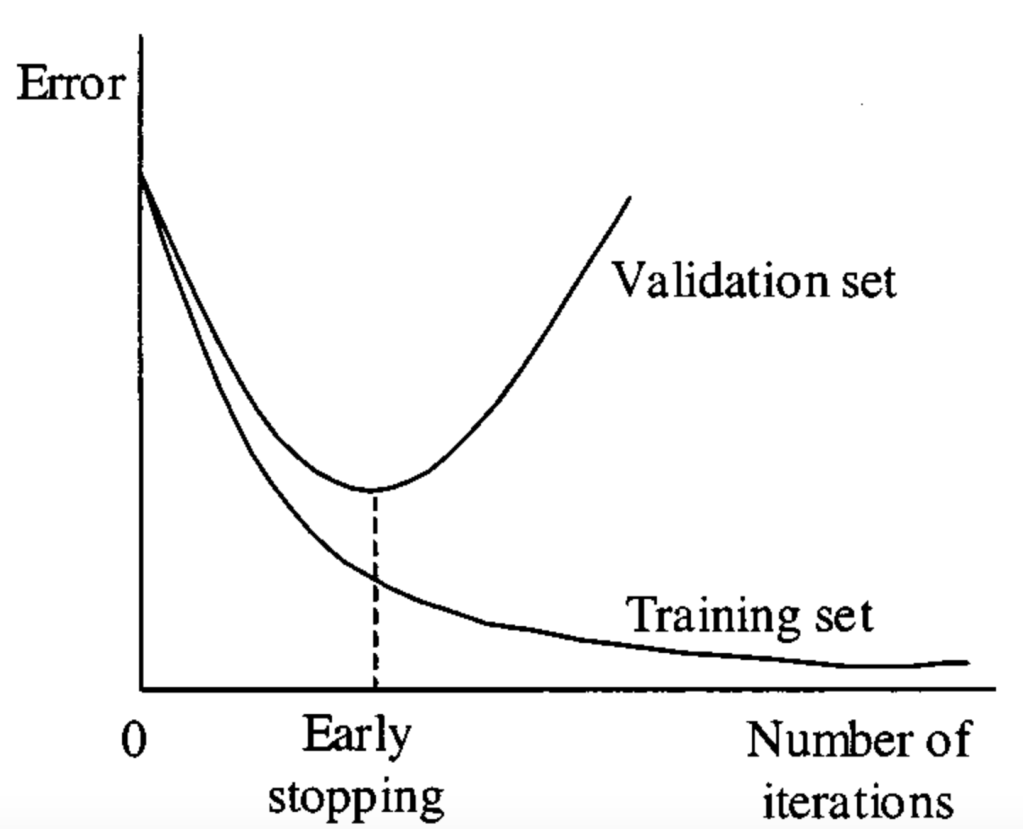

What I show in my article is that machine learning researchers, while drawing on this history, conceptualized error in a different way in the twentieth century. Rather than conforming to a single, normally distributed law, different complex distributions of errors could be modeled iteratively, improving predictive performance over time. The image below depicts a typical training process in machine learning, where the error rate decreases over time. The use of the historical term “epoch” to describe a model’s iterative pass through the entire set of training examples gestures to the “processual” sense of error assumed in machine learning.

A common representation comparing error rates on training and validation sets in machine learning. Image: Ramazan Gençay via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0).

Although it is difficult to know exactly what Foucault meant by “errors” of life, I feel that it shares something with this machine learning training process, in which “performance” (if not knowledge or truth) is engineered by propagating errors across a model’s weights. In a way, this process of searching for a minimum across the “error surface” of the training distribution even evokes error’s ancient meaning of wandering or roaming—connecting it to a much longer cultural history represented in Winslow Homer’s 1899 painting above.

The article concludes with a gesture towards the normative implications of this more recent sense of error. While the earlier period valued the moderation and perfection of the median, around which errors were normally distributed, what we see emerging in machine learning is the use of error to define and evaluate the performance of both models and humans on various learning “tasks.”

Here, error rates take on a genuinely anthropological dimension—drawing and redrawing borders between the capabilities of humans and models. New machine learning models are being continuously evaluated against human capabilities on these tasks—from coding to creative writing.

This has consequences beyond just when models get things wrong or “hallucinate.” Whenever you use ChatGPT, every text or image that it produces has emerged from a process of gradually correcting errors in predicting sequences of words. In a very real sense, error—here the difference between the correct and incorrect element in a sequence of words—is redefining language itself.

Alexander Campolo is a Postdoctoral Research Associate on the “Algorithmic Societies” project in the Department of Geography at Durham University. His current research draws from the history of science and technology to explore epistemological and political implications of machine learning. He received his PhD from New York University and has previously worked at the Institute on the Formation of Knowledge at the University of Chicago and the AI Now Institute.

- Georges Canguilhem. The Normal and the Pathological. Translated by C. R. Fawcett. (New York: Zone Books, 1991). ↩︎

You must be logged in to post a comment.