Hatching Schemes in The School of Projects

Read Vera Keller, Ted McCormick & Kelly J. Whitmer’s introduction to their special issue “Knowledge and Power: Projecting the Modern World” here.

Vera Keller, Ted McCormick & Kelly J. Whitmer

Projects are so common today that it’s easy to take them for granted. In the early modern period they were recognizably new. The identity of a “projector” (or, later, “project-maker”) appeared in Europe at the turn of the seventeenth century, and was associated with individuals who dabbled in many different crafts and enterprises.

We chose the image The School of Projects (1809) as the cover for our recent JHoK special issue on the role of projects in the history of knowledge because this satirical print — which falls roughly in the middle of the period covered by our issue — highlights some features of projects that have persisted over four centuries.1 In particular, the way this satire links financial speculation, colonialism, and planetary catastrophe draws attention to how projectors past and present have framed the relationship between knowledge and global disruption.

Samuel De Wilde, “The School of Projects,” The Satirist (London: Tipper, 1809). Wellcome Collection 38405i (public domain).

Our special issue gathers together essays that explore particular historical contexts in depth, while highlighting larger themes of risk-taking, violence, and malleability of opportunity or situation that have continually informed the history of projects. These themes likewise color The School of Projects, which originally appeared in an October 1809 article of the same name by Samuel De Wilde, the artist who produced the print. De Wilde published “The School of Projects” under the pseudonym Thaumaso Scrutiny in the Satirist, a monthly periodical edited by George Manners, to which De Wilde regularly contributed. The Satirist frequently lampooned projectors and had already attacked in other issues some of the figures De Wilde depicted in The School of Projects.2

De Wilde describes a group of projectors looking to found a new investment opportunity, the “Lunatic Company,” promising such disruptive technological interventions as boring through the planet and building a bridge from the Earth to the moon: in short, a kind of early nineteenth-century SpaceX. “Where the progress of human ingenuity will be at last arrested, it is not easy to foresee,” De Wilde writes. However, as he slyly observes, “the professors of the School of Projects seem resolved not to be discouraged by the common obstacles, which they, who are conversant only with the laws of nature, term impossibilities.” Mere science was no match for the projector’s promises.

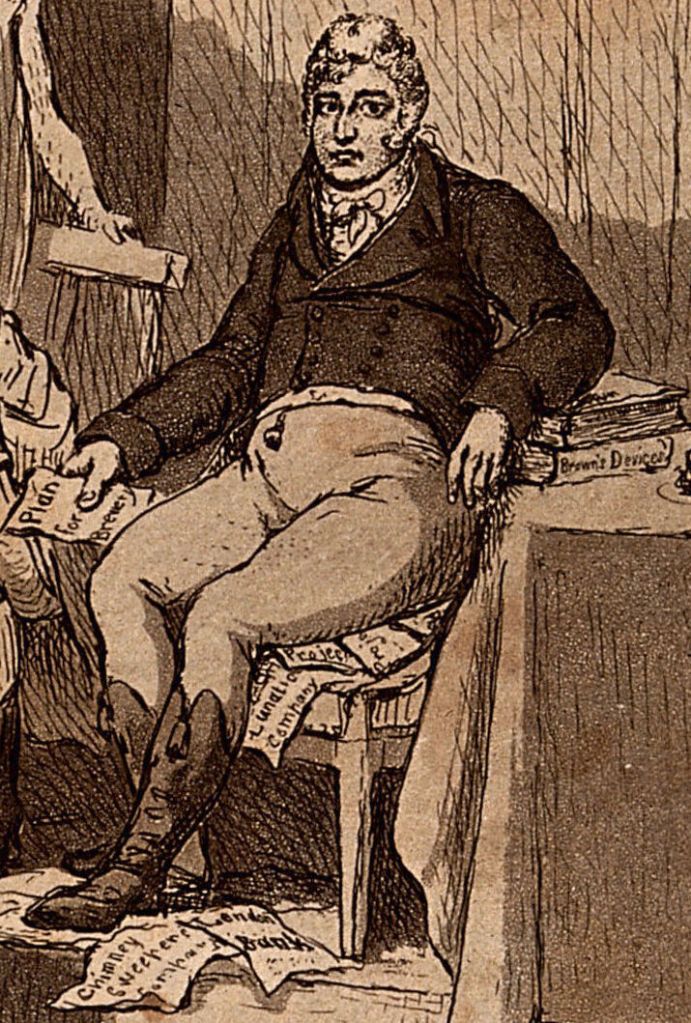

In the foreground of the image, we see these “professors.” To the right sits William Brown, “president” of the school and real-life proprietor of the London Genuine Beer Company, holding a paper entitled “Plan for Brewery.”

Detail from Samuel De Wilde’s print, “The School of Projects,” showing William Brown.

So many other paper plans spill out from beneath his behind, that Brown, with his constipated expression, seems to be “hatching them” according to the Satirist, in an apparent visual pun on the notion of hatching a scheme. Looking more closely at the overall print, we soon notice papers stuffed into the pockets of three of the other projectors, a reminder that projects were not merely mental conceptions or rhetorical frames, but a concrete textual genre that still abounds in many personal and state archives today.

Next to Brown, another figure force-feeds one such paper to a ram, a reference to a scheme to breed immense sheep.

Detail from Samuel De Wilde’s print, “The School of Projects,” showing George Leyburn force-feeding paper to a ram.

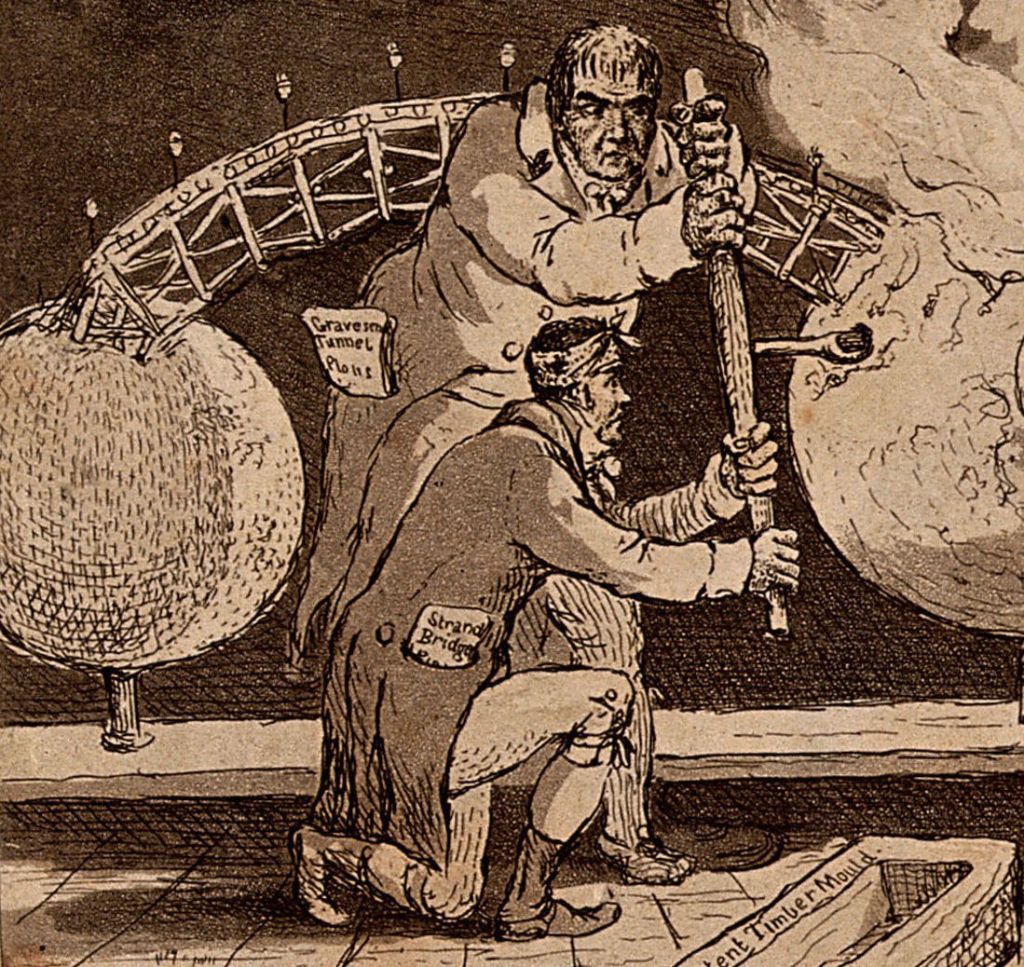

De Wilde describes this sheep projector as a “projecting butcher” and one of the “principal advocates and supports” of Brown’s multiple schemes. George Leyburn, a butcher in Leadenhall Market, served as one of the directors of William Brown’s Cattle Life Insurance Company and a participant in his Hope Fire and Life Assurance-Office. The paper Leyburn is stuffing into the ram’s mouth is labelled “Vauxhall Bridge Sh[ares?].” This refers to a bridge company speculation founded by Ralph Dodd, one of the two engineers shown gouging into the Earth on the left of the image, another recently failed scheme for a “Gravesend Tunnel” protruding from his pocket.

De Wilde wove references to these men’s mutual ties throughout his article. These projectors wound one untried, ambitious project around another, amplifying both scale and risk.

William Brown had founded his massive brewery in 1804 through a new means of raising funds by selling shares. By 1807, Brown lit his brewery (so large that he held a dance for 150 people inside a 7,000-barrel vat) with the coal gas technology developed by Frederick Windsor, pictured at the center of the print — with a blazing gas-pipe in hand that could at first glance be a pitchfork, or perhaps Windsor’s own forked tail. Brown also tried the “experiment” of running a pipe with gas from a furnace in the brewery to the neighboring streets.3

J. S. Barth, active 1797–1809, A View of the Genuine Beer Brewery, Golden Lane, 1807, Aquatint, hand-colored, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1977.14.18319 (public domain).

Even if each man seems preoccupied with a different detail in the picture, De Wilde suggests that all were “occupied in one grand project,” a “scheme” of “vast and incalculable importance to the British empire.” This was nothing less than “to build a bridge from the Earth to the Moon,” with materials dug out by making “a grand tunnel towards the centre of the earth,” with further holes promised to points of interest anywhere on the surface. Bridge and tunnel linked lunar and terrestrial colonization with a host of lesser schemes:

[the] patentee of the gas lights had engaged to light up the tunnel and the bridge: another projector had constructed a carriage to cross to the Moon which would go without horses.

It might not be immediately obvious how sheep breeding, brewing, and insurance plans fit into this, but any project this big would surely consume beer and mutton, to say nothing of the risks it would incur. It might also lead to “the discovery and establishment of [new] market[s] for [these] commodities”.

Detail from Samuel De Wilde’s print, “The School of Projects,” showing two engineers gouging into the Earth.

This preposterous scheme exhibits features of projects that were long familiar in the early nineteenth century and persist in the world of venture capital and disruptive technologies today. As the articles in our special issue detail, projectors regularly played down failure while playing up the ambitions and emotions of risk-taking and violence. They bound ideas of the public good to their vision of the future, silencing objections and dismissing alternate perspectives as distorted either by self-interest or ignorance — much as the Lunatic Company in the Satirist insisted on the “vast and incalculable importance” of their scheme “to the British Empire,” and pooh-poohed any would-be naysayer as a “dull hacknied wit.”

This is reminiscent of today’s projectors of generative “AI”, who tout the inevitability of its triumph and the consequent importance of its adoption — indeed, the public duty to promote it — in all spheres of life. Then, as now, projectors claimed not only an agency but also a vision that their critics, almost by definition, lacked.

What projectors claimed to see were connections between apparently distant, unrelated, or disproportionate phenomena: digging a hole, as it were, to get to the moon. The center of this scheme — that is, the center of the Earth itself — illustrates another theme highlighted in our issue: the importance of situation in underwriting the promises of transformative intervention. Rather than grounding their interventions in a specific surface locale, the projectors dig to a point from which every location on earth is within reach by the same means, and which brings even the moon within humanity’s grasp.

If projects determined the future, they also left the details of that future — the moments in time and the places on earth where it would burst forth with all the violence of Windsor’s exploding furnace — radically and, in The School of Projects’ critical view, menacingly open.

Detail from Samuel De Wilde’s print, “The School of Projects,” showing Frederick Windsor with a blazing gas-pipe in hand.

Should our currently touted AI futures prove as illusory and costly as some of the projects in these men’s pockets did, it is not clear who will pay, or what will stop the next round of projects from wreaking still greater havoc. Indeed, despite endlessly refreshed claims of innovation and progress, what is striking about this set of projectors is how little in their cultural stance, and even in the details of their imagined futures, was truly new — and how much of their world remains with us today.

The fact that projects have endured, despite continual satire and frequent popular outrage, suggests how deeply the dynamics of knowledge that projects project have become part and parcel of modernity. Without sustained critical attention to projects as a genre and as an historical phenomenon, we unwittingly further those dynamics.

Vera Keller, Professor of History at the University of Oregon, works on early modern Europe. She has published Knowledge and the Public Interest, 1575–1725 (Cambridge University Press, 2015), The Interlopers: Early Stuart Projects and the Undisciplining of Knowledge (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2023) and Curating the Enlightenment: Johann Daniel Major and the Experimental Century (Cambridge University Press, 2024).

Ted McCormick is Isobel Haldane Professor of History at the University of Pennsylvania. He is the author of William Petty and the Ambitions of Political Arithmetic (Oxford University Press, 2009) and Human Empire: Mobility and Demographic Thought in the British Atlantic World, 1500–1800 (Cambridge University Press, 2022).

Kelly J. Whitmer is Professor of History at Sewanee. Her first book, The Halle Orphanage as Scientific Community: Observation, Eclecticism, and Pietism in the Early Enlightenment was published by the University of Chicago Press in 2015. Her new book, Useful Natures: Science, Pedagogy and the Power of Youth in Early Modern Central Europe, is forthcoming.

- The image is available via the Wellcome Collection. It is further discussed by the Science Museum and by James Taylor in Creating Capitalism: Joint-Stock Enterprise in British Politics and Culture, 1800-1870 (Woodbridge, UK: Royal Historical Society and Boydell Press, 2006), 97. ↩︎

- The Satirist lampooned William Brown in “Cornucopiana” (April 1809), 348–351 and “Cattle Insurance” (June 1809), 566–575 and would again in “A Brief Reply to W. R. H. Brown,” (October 1809), 376–381. It also attacked Ralph Dodd in another essay in the same issue, “Modern Projectors” (October 1809), 368–375. ↩︎

- Alan Pryor, “The Industrialisation of the London Brewing Trade: Part III,” Brewery History 165 (2016), 51–80.

Anon., “Some Account of the Experiment made at Golden-Lane to illuminate Streets by Coal-Gas Lights,” The Athenaeum (1807), 187–188. ↩︎

You must be logged in to post a comment.