The Economy versus the People in Eighteenth-Century England

Read William Cavert’s research article “The Improvement Police: Nehemiah Grew on Knowledge, Nature, and Power” here.

William Cavert

University of St. Thomas — Minnesota

In the twenty-first century, “the economy” is a subject of frequent discussion in the news and politics. Here, it is usually assumed that we can measure “the economy” as growing or shrinking, getting better or worse, and that such labels aggregate a collective experience: if the economy is good, most of us are doing well.

But even a moment’s consideration of this raises questions, since working and getting, or expending money can bring suffering as easily as happiness. Once we realize that this term can measure some things better than others, historical questions emerge: when did discussions of “the economy” begin, and why?

One ancestor to our modern conception of “the economy” is found, surprisingly, in discussions of “the public” during the Enlightenment. We often view eighteenth-century Europeans as interested in the public sphere or public opinion in ways that might lead towards reform, or even revolution. But “the public” could also be understood as a concept that would strengthen rather than weaken monarchies.

One especially dramatic example of this is a lesser-known treatise written by a plant scientist, which imagines how England’s government could grow rich and powerful by controlling almost all aspects of life. This would be good for “the public,” the treatise assumes, but whether it was wanted by the actual people is not discussed.

The scientist and author in question was Nehemiah Grew, best known for his pioneering research in botany and his role as keeper of the Royal Society’s collections during the late seventeenth century – the age of Newton and Boyle, when England was at the forefront of a new model of public knowledge creation about the natural world.

Nehemiah Grew (1641-1712), as depicted in a portrait from his 1701 work Cosmologia Sacra: or a Discourse of the Universe as it is the Creature and Kingdom of God (public domain).

After decades of this work, Grew submitted his treatise to Queen Anne in around 1706, entitled “The Means of a Most Ample Increase of the Wealth and Strength of England.” There he proposed ways for England to become rich and powerful through the improvement of its farming, manufacturing, and trade. Each of these themes was understood very broadly to include even private choices with economic implications. Marriage, for example, led to reproduction, which in turn impacted the labor supply, so families and sexuality were to be regulated. Work was too important to escape government attention, as were consumption, estate management, scholarship, prices, and migration.

A cornerstone of Grew’s approach was state support for, and control over, a new network of school-museum-archives. Each locality in England would have a teacher of farming and land management, who would demonstrate practical techniques through a museum displaying all existing inventions, machines, and technologies. A library of practical farming would demonstrate best practices, which would be required according to legally binding leases, all stored in the local archive.

This was highly ambitious (indeed, arguably wildly unrealistic), given that England had no state education system, nor did it offer formal technical education in any school or university. But Grew ignored this and, even more remarkably, pretended that adequate expertise existed to advise farmers and manufacturers. While there was a growing body of “improvement” literature offering advice about what to plant, how, and where, most of it was provisional, speculative, or controversial — which Grew ignored by presenting it as settled and authoritative.

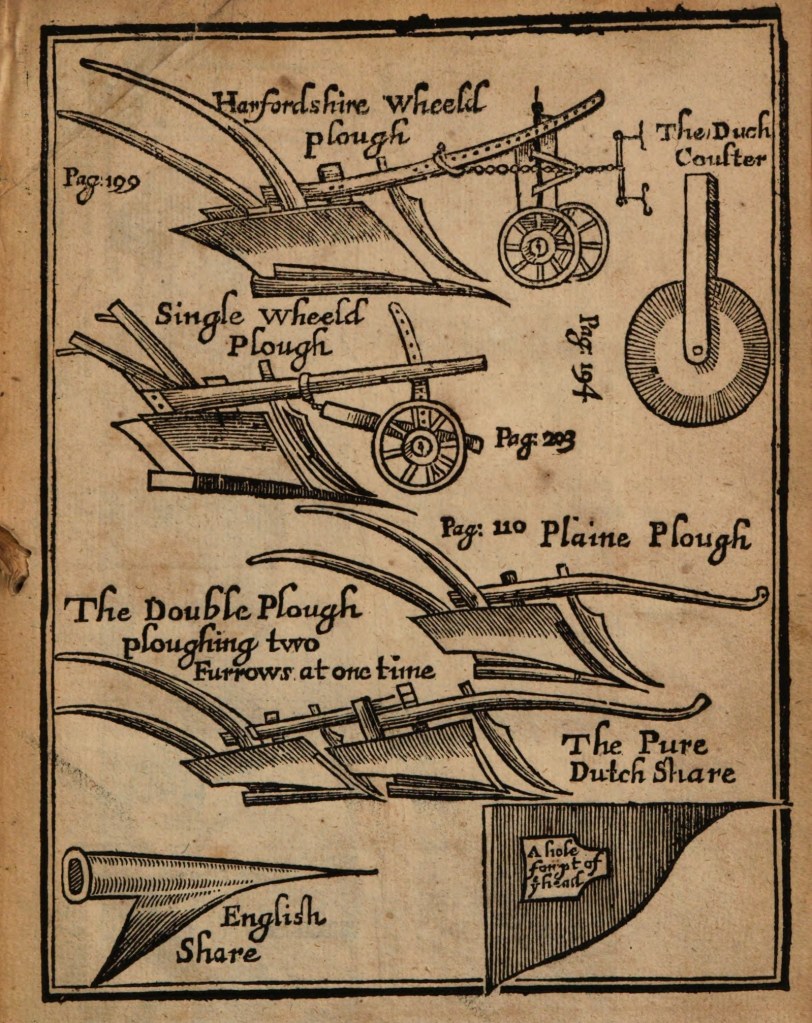

A page showing varieties of plow from Water Blith’s English Improver Improved (1649), one of the improvement treatises that Grew used and imagined as a basis for his school-museum-archives. Image: Hathi Trust (public domain).

By pretending that settled and authoritative scientific knowledge existed for all aspects of farming, industry, and trade, Grew simply assumed that the state could mandate universal acceptance of these best practices. Usually, “improvement” during this period was seen as voluntary, but Grew wanted something which can be labeled an “improvement police,” as I argue in my article in this year’s JHoK special issue. State authority would mandate what landowners should plant, how manufacturers should work, where traders should sell, whether people should marry, what they could buy and wear, and much more. Grew never described the punishments that would underlie such requirements (fines? imprisonment? execution?); like most “projectors” of the early modern period, he presented his most invasive proposals as common-sensical and uncontroversial.

Why would a government take such intrusive measures? Because doing so would benefit “the public.” This term was applied in a particular way in Grew’s treatise: it was the financial health of the realm, the positive trade balance, and the booming state revenues his plans would produce.

This version of “the public” was indistinguishable from the Queen’s income. It could be easily measured and analyzed, it could grow or decline. In one telling passage, Grew notes that when “people” waste time drinking, “the public” loses out because those “people” are not working. The question is not whether drinking is good or bad for their health or happiness, but what contributes or detracts from quantifiable productivity. “People” were part of “the public” when working, selling, or buying, but not otherwise.

While modern economists today have far more sophisticated tools for assessing such actions, this basic assumption has persisted: the economy, like Grew’s public, is what can be counted and, potentially, tapped by a state. For Grew, and for his contemporaries who helped develop this approach, that which could not be counted (joy? community? stress? virtue? love?) mattered as little as the punishments which would be required to force people to improve themselves.

William Cavert is Associate Professor of History at the University of St. Thomas in St Paul, Minnesota, USA. His research focuses on the environmental history of early modern Britain, including pollution, energy, climate, animals, and economies.

You must be logged in to post a comment.