The Paper Power of Projects: Great Designs and Making America “Great” Again

Read Vera Keller’s research article “Great Designs and Global Colonialism: Sir Balthazar Gerbier (1592–1663), El Dorado, and the Transnational Politics of Knowledge” here.

Vera Keller

University of Oregon

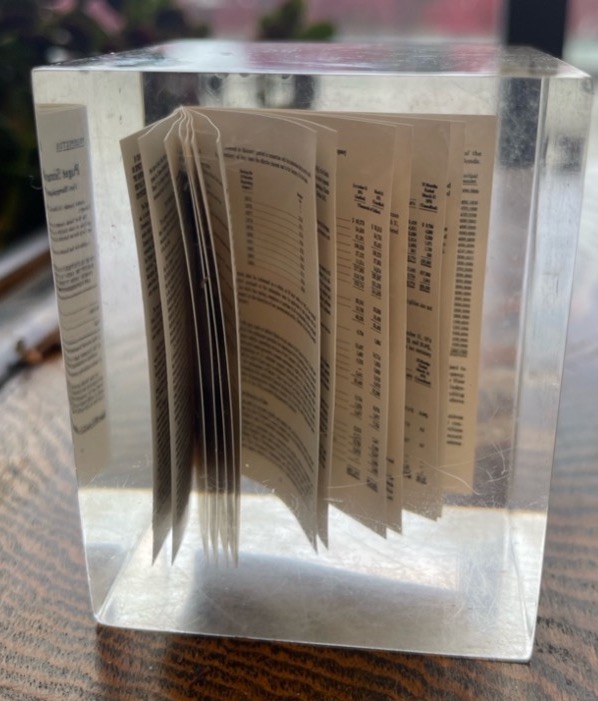

On my desk sits a vintage paperweight. A cube of acrylic encases a miniature prospectus from 1975 for thirty million dollars in bonds issued by the Puget Sound Power & Light Company via two New York City banking firms. Perfectly crystalline, geometric, and apparently rational, this tiny object radiates power captured from the mighty rivers dammed throughout the Pacific Northwest and in the streams of capital pouring out of the nation’s financial center.

A vintage paperweight. Photo: Author.

New York City in 1984. Photo: Lars Plougmann, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Held and turned in the hand, its pages splayed open, the entombed prospectus gives a feeling of control and access. Here in microcosm is Manifest Destiny, the idea that the United States, once a small band of European settlements along the Atlantic littoral, was fated to occupy vast territories across North America, with nature conquered, project by project, from sea to shining sea.

The paperweight embodies the aesthetic of high modernism, that coolly rational self-confidence that comes from believing one is obviously right. Such projects were seen as paving an ineluctable path of progress, pioneering and heroic, blazing forth the fate of the nation. Control over water through damming megaprojects served as a keystone of the US takeover of indigenous territories throughout the American West, whether in the arid South or water-rich North. As an investor in such bonds, I too might be assured of my own path to private success, as well as my role in the public good, taming and settling the continent.

Paperweight. Photo: Author.

The idea of progress and high modernism has long been in the crosshairs of historians, particularly historians of science and technology. For many decades, they have called out the colonial ideologies at play, the destruction of indigenous sovereignty and knowledge, the vast environmental consequences, and the lack of attention paid to the long history of failure. Yet they have not focused on the genre of the project itself in all this, even though, as many of the articles in this year’s JHoK special issue have argued, practices of projecting played a critical role in constructions of modernity.

As I argue in my own article in the special issue, a particular form of project, the “Great Design,” served as an ideological linchpin in views of modern progress. Today, great designs remain embedded not only in history education in schools but even in professional scholarship. In particular, they function as foci of debates in national scholarship; they are live-wire historiographical topics because they touch on the perceived greatness of various nations and, by extension, the greatness of those nation’s historians.

Like my paperweight, these historiographical “Great Designs” are entombed in the amber of a particular moment. They are objects forged not so much at the time of their putative creation in early modernity, but rather in the retrospective historiography of the nineteenth century. According to such accounts, great designs were brilliant plans hatched by chief statesmen like Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, Oliver Cromwell of England, or Napoleon of France. The ambitions of these great men directed the course of history. Even as current historiography rejects this great man school of history, “Great Designs” have been embedded in curricula and scholarship for so long that they continue to hold sway.

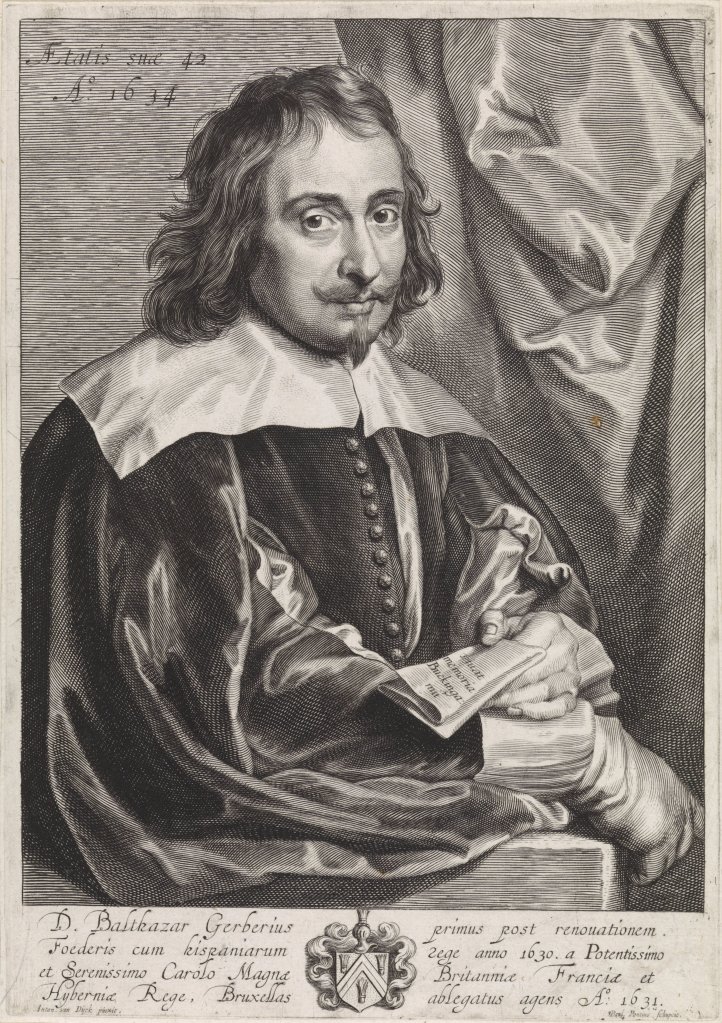

My article resituates such great designs in the context of projecting. Rather than the brainchild of political genius in the nation’s nerve center, the great design, I argue, was a period intelligence product cobbled together through the paper practices of transnational agents. Intelligencers such as Sir Balthazar Gerbier (1592-1663) made a profession out of vending highly ambitious projects to many rival clients. They drew upon other paper practices at the time, collecting, cutting and pasting, and communicating recipes or “secrets” on a wide variety of topics, from the medicinal to the political.

Paulus Pontius after Anthony van Dyck. Portrait of Balthazar Gerbier at the age of 42. 1634. Engraving on Paper. Image: Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-33.307 (public domain).

Gerbier, as the English resident agent in Belgium, regularly sent intelligence dispatches to the Secretary of State, Dudley Carleton (1573-1632), and his much less sympathetic successor, John Coke (1563-1644). When Gerbier feared that Coke might get him recalled from his position, he wrote, “I am wholy settled in this way of papers, my hopes therein to continue, as my Element.”1

By “this way of papers,” Gerbier is referring to the constant stream of papers flowing from his desk. He funneled intelligence constantly to Coke, but also to many other recipients in the English Court and abroad. His clients perused papers describing bold schemes traversing wide swathes of the planet’s surface, such as a project to found a new state in America, which was purportedly based on stolen Spanish intelligence detailing the location of indigenous American alchemists who could produce gold and precious gems.

Part of the intelligencer’s repertoire included scene-setting and emotional management, such that these proposals were read in charged environments. The idea that other clients were considering similar designs only increased the pressure to seize the moment. As high-risk ventures, such schemes were assured neither by Providence, nor by previous histories of success.

As we today wrestle daily with the consequences of the project-fueled ideology of progress, such as global warming, the failures of projects have become all too visible to us. To take just the example of my paperweight, due to the dams built by the Puget Sound Power & Light Company (funded by bonds), Baker River sockeye salmon were critically endangered by 1992. The cultural and natural importance of salmon to the vast region of the Pacific Northwest cannot be overstated.

Lower Baker Dam, a 1925 hydroelectric project by the Puget Sound Power & Light Company on the site of a fishing village belonging to the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe. The Baker River is home to a genetically distinct sockeye salmon. Photo: Jon Roanhaus, 2014, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Too often, as Ted McCormick, Kelly Whitmer, and I discuss in the forthcoming introduction to our JHoK special issue, projects produce problems that appear to require ever greater projects to solve. In my area of the Pacific Northwest, some of the recent solutions to salmon extinction proposed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers included an untried billion-dollar project to vacuum up salmon. On the Baker River in Washington State, through pressure by the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe on Puget Sound Energy (the current incarnation of the Puget Sound Power & Light Company), salmon runs are recovering, but that has required extensive interventions involving hatcheries and fish transports.

De-development is almost never on the table. Though it was, finally, in the historic, lengthily negotiated 2023 Resilient Columbia Basin Agreement between four Columbia River Basin tribes, the US federal government and the US states of Washington and Oregon. That plan might have included the breaching of four dams on the Snake River.

In June 2025, President Trump signed a presidential memorandum entitled, “Stopping Radical Environmentalism to Generate Power for the Columbia River Basin,” that withdrew the US government from the agreement. As part of the Trump administration’s project to “Make America Great Again,” this is a great design if ever there was one.

Vera Keller, Professor of History at the University of Oregon, works on early modern Europe. She has published Knowledge and the Public Interest, 1575–1725 (Cambridge, 2015), The Interlopers: Early Stuart Projects and the Undisciplining of Knowledge (Baltimore, 2023) and Curating the Enlightenment: Johann Daniel Major and the Experimental Century (Cambridge, 2024).

- National Archives, UK, SP 77 26, 164. ↩︎

You must be logged in to post a comment.