What Makes a Project Good or Bad? Lessons from Early Eighteenth-Century Germany

Read Kelly J. Whitmer’s research article “Youth, Happiness, and Institutional Projects in the Early Eighteenth-Century German Lands” here.

Kelly J. Whitmer

Sewanee: the University of the South

Workhouses, poorhouses, orphanages, charity schools — German cities in the early eighteenth century were awash with new institutions that promised to solve various social problems. They frequently targeted young people. Why? One reason is that there were generally more of them living in cities compared to other age groups. Another is that “youth” were widely regarded to be happier and more malleable than the old, making them ideal populations to house in spaces devoted to correction, instruction and, ultimately, transformation.

These new institutions functioned (i.e. had food, wood and other necessary supplies) thanks to the invisible labor of figures like Peter Kretzschmer, a professional estate manager (Oeconomicus) who worked for many years as a caterer in the city of Halle’s orphanage, before transferring to Leipzig’s orphanage in the 1740s.

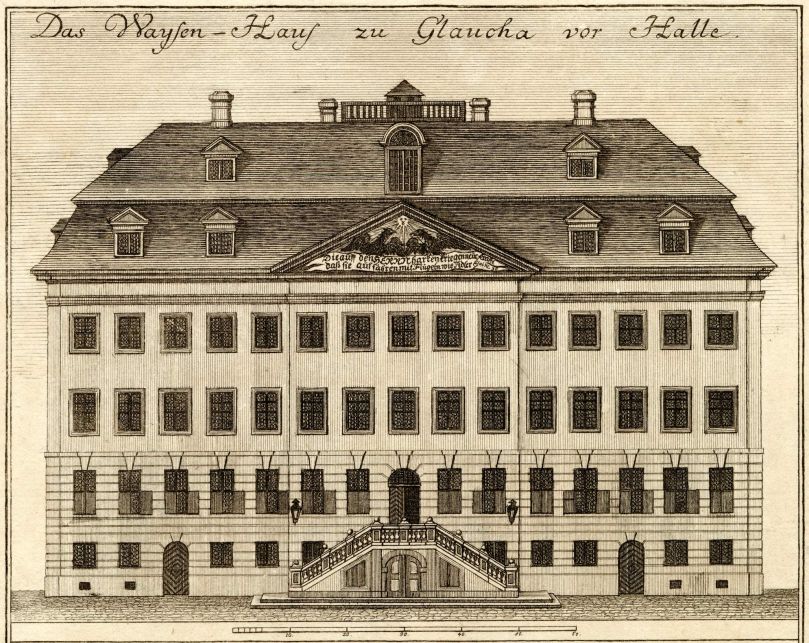

Engraving of the Halle Orphanage, where Peter Kretzschmer was a caterer in the 1720s and 1730s. Engraving by Gottfried August Gründler, 1749. Image: Archive of the Francke Foundations, Halle/Saalem (public domain).

While we know little about Kretzschmer’s life story, we know for sure that he rubbed elbows with many of early eighteenth-century Germany’s movers and shakers: the philosopher-mathematician Christian Wolff, the Pietist theologian August Hermann Francke, as well as the well-known Professor of “Economics” (Oeconomie) and “Cameral sciences” (the study of economic policy and state administration) Georg Heinrich Zincke.

Zincke had both studied and taught at the University of Halle in the 1720s, but became enmeshed in a court controversy that landed him in prison. He was eventually pardoned and moved to Leipzig in 1740, where he taught at the university and became involved in an effort to further academize the study of Oeconomie, aiming to make it accessible to university students. He likely met Kretzschmer in Halle, and by 1744 both men were living in Leipzig. It was in this year that Kretzschmer’s book of “Oeconomic Suggestions” was published.

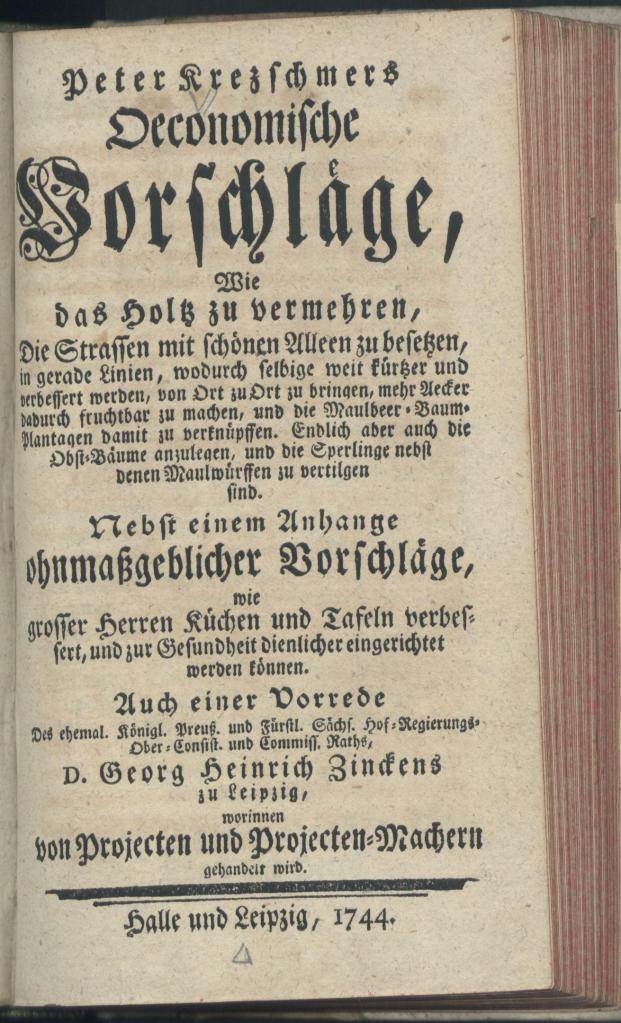

“Oeconomic Suggestions” was basically a collection of “projects,” a term used in this period to describe strategically directed efforts to respond to complex problems, such as deforestation or an unnavigable waterway, and intended to have a transformative effect on the future. Kretzschmer’s projects included a targeted response to a regional wood shortage, for example, as well as a mass die-off of local fruit trees. Zincke signaled his support of Kretzschmer’s projects and his legitimacy as a “Project-maker” (or “Projector”) by writing the book’s preface.

Title page of Peter Kretzschmer’s Oeconomische Vorschläge, a collection of projects that also included a short preface “On Projects and Project-making” by Georg Heinrich Zincke. Published in Halle and Leipzig in 1744. Image: SLUB Dresden, Digital Collections, 39.8.5362,angeb.3 (public domain).

For Zincke, writing the preface was an opportunity to defend projecting or project-making, which at the time had a beleaguered reputation in the German lands. Despite the ongoing efforts of defenders of projecting, among them Johann Joachim Becher and even Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, “project-makers” were frequently vilified and described as untrustworthy individuals who stole from other people’s ideas — in other words, men to be avoided at all costs.

A pretty characteristic example of this negative framing appears in the “projectmaker” entry of Johann Heinrich Zedler’s popular Universal-Lexicon of all sciences and arts (1741), which informed readers that:

Project makers are those who discover this or that project, which they often pretend to be the originators of, and encourage its realization because they expect a big profit to be made from it. One should not listen to this kind of person because generally they are out to deceive others…1

Against this backdrop, Zincke used his preface to Kretzschmer’s “Oeconomic Suggestions” to chart a different course. He argued that “projecting” should be taught and standardized in academic environments, noting that projects were particular kinds of texts that always contained the same four universal components:

- a summary of the problem and potential solution (die Sache)

- a rationale or the “reasons for action” (Bewegungsgründe)

- a discussion of previous (usually unsuccessful) attempts to address the specific issue

- a description of likely objections (Einwürfe)

Anyone who has ever written a project proposal will recognize that yes, these are indeed all components that need to be unambiguously addressed!

Emphasizing these components helped Zincke support the idea that projecting was a “natural” and universal human activity designed to bring about happiness. Instead of dwelling on the inherently disruptive, risky and extractive aspects of projecting, Zincke focused instead on the projector’s intent and personal character.

For Zincke, in other words, the question of whether or not a project was good or bad, happy or harmful, came down to questions of intent and the “true” meaning of happiness, something that young people, many argued at the time, seemed best able to embody in a genuine way. Since character formation remained a central aspect of ongoing educational reform efforts in the German lands throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries — including efforts to reimagine higher education by creating alternative schools and programs that could train a new generation of projectors —young people were at the very center of these efforts to “virtuize” projecting.

Zincke acknowledges in his preface that some projectors are in fact “deceitful” and “malicious.” He laments the “creativity and skill” that is wasted on malevolent projects more generally, while also signaling his frustration with what in the German lands was often called “wind-making” (Windmacherei)— a derogatory term associated with charlatanism, referring to projectors who claimed to be able to accomplish impossible things like generating artificial winds or producing machines for walking on water.

Engraving of Georg Heinrich Zincke by Johann Christoph Sysang. Image: Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, Inventar-Nr. A 24847 (CC BY-SA 3.0).

In keeping with the arguments I explored in my article in this year’s JHoK special issue, Zincke stressed that clever youth (“students of wisdom”) were especially well-placed to recognize the potential of any project to generate happiness, even those developed by “evil schemers.” The problem, he insisted, was not with projecting itself; instead, it was with the intentions of “bad sorts of people.”

Zincke also stressed that “evil schemers” were really only one type of projector. Most didn’t mean any harm, he argued; they were simply sloppy or uninformed. Even sloppy projects, he argued, “seek all that is good and use only good means, or if it were possible or practical under the circumstances, they truly seek and propose nothing but good.” But goodness, like happiness, is not self-evident nor well-defined. Simply because a projector claims to be a good person and is invested in generating happiness does not necessarily mean that this will be the ultimate outcome.

In the end, Zincke’s efforts to turn contemporary debates about the ethics of projecting itself into a debate about the character of the projector were largely successful. As shown in the recent JHoK special issue, projects have become so tightly woven into the structural fabric of our daily lives that they seem both normal and necessary. Those of us in academic environments often structure our careers around the realization of publication projects and other initiatives. Meanwhile, examples of larger scale projects — such as the building of a new high-speed railway system in California, or efforts to construct massive complexes for biotechnical research and manufacturing — abound.

Yet, when projects cause harm, the general tendency is not to blame “projecting” itself but the people involved, assessing their intentions, integrity or the amount of effort they put into realizing the project itself. Many of the institutional projects I mentioned earlier — workhouses, poor houses, orphanages, charity schools — were implemented by people who genuinely considered themselves to be doing “good.” Yet, we know now that these institutional projects were often exceedingly harmful.

Instead of the projector, perhaps the time has now come to blame projecting itself — or at least to approach it more critically. In response to Zincke’s claim that the value of a project comes down to how kind, good or well-intentioned the projector is, we might consider the ways in which the phenomenon of projecting perpetuates a system of unequal power relations that privileges the project-maker’s intentions above all else. Projects operate within a framework in which people, spaces and things are projected upon, forcibly disrupted and even expected to transform, whether they want to or not.

Kelly J. Whitmer is Professor of History at Sewanee. Her first book, The Halle Orphanage as Scientific Community: Observation, Eclecticism and Pietism in the Early Enlightenment was published by the University of Chicago Press in 2015. Her new book, Useful Nature(s): Science, Pedagogy and the Power of Youth in Early Modern Central Europe is forthcoming.

- “Projectenmacher” in Johann Heinrich Zedler, Großes vollständiges Universal Lexicon Aller Wissenschafften und Künste Band 29 (Halle und Leipzig: Verlegts Johann Heinrich Zedler, 1741), 784. ↩︎

You must be logged in to post a comment.