From Chance Encounters to Fresh Insights: Serendipity at Work in Historical Research

Read Christine Keiner’s research article “The Nuclear Sea-Level Canal Engineering Feasibility Field Studies and Epistemic Risk in the Darién, 1965–1970” here.

Christine Keiner

Rochester Institute of Technology

I have had the amazing good fortune to work as a historian of science for over twenty years. Flowing through my various articles and books is the question of how science and environmental politics shape each other. My PhD advisor Sharon Kingsland encouraged me to explore this relationship whilst researching the cultural history of Chesapeake oyster conservation. Ever since, I have enjoyed delving into what historian Stephen Bocking calls “the changing political role of scientific expertise,” and thinking about how historical knowledge can inform current environmental policy initiatives.1

My article in the 2025 special issue of JHoK is an offshoot of my second book, Deep Cut. Published in 2020, the book deals with Cold War-era debates over plans to replace the Panama Canal with a seaway created using peaceful nuclear explosives—a so-called “Panatomic Canal.” In particular, it highlights the role that marine and evolutionary biologists played in raising awareness about the risk that the megaproject could unleash waves of invasive species by connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans for the first time in three million years.2

While conducting research in Panama City during the early 2010s, I came across an artwork which I could now relate to this key aspect of the sea-level canal controversy of the late 1960s. It was a mola—a textile that Guna women in Panama create, wear, and often sell to tourists.3 I bought many gorgeous molas from Guna artisans, but one in particular seemed to have been made just for me, given what I was working on. It depicts two serpents facing one another across a maze, reminding me of the debates surrounding the Panatomic Canal and whether it would enable sea snakes to cross the two oceans and wreak ecological and economic havoc. This beautiful work of art would continue to inspire me throughout the difficult process of writing the book.

The author holding an inspirational serpentine mola purchased from a Guna artisan in Panama City. Photo: Sonia Keiner.

Another source that inspired me during my research for Deep Cut appeared just as serendipitously. Paging through a 2016 issue of the American Historical Review, I came across Philipp Lehmann’s article on Atlantropa. As Lehmann’s article explains in fascinating detail, Atlantropa’s proponents sought to build a massive dam across the Strait of Gibraltar, intended to generate huge amounts of hydroelectric power and create a vast new landmass linking Europe and Africa. Lehmann frames this saga—which spanned over two decades—as a case study in “the still-understudied history of unrealized utopian projects of high modernism.”4

Researching unrealized projects of the past like Atlantropa and the Panatomic Canal is far from trivial. Contrary to what a snooty historian once told me at a conference, it is not true that “any one of us fools can study the history of failed projects!” As articulated by geographer Michael Heffernan, who has himself researched late nineteenth-century French colonial plans to transform the Sahara Desert into a vast inland sea and railway network:

Unsuccessful initiatives, especially controversial and long-running ones, tend to leave an archival legacy that is more complex and extensive than realized projects. Failures allow the historian to chart the limits of our faith in science and technology.5

Insights like these helped me bring order to the chaos of my sprawling study. The concept of “unrealized projects” helped me understand the never-built nuclear waterway not only as a propaganda tool—a role it indeed played for US officials during the Cold War—but also as a vehicle for charting the rise of scientific and political awareness of marine invasive species.

In fact, I found so much interesting material about the unbuilt nuclear sea-level canal that I wasn’t able to include it all in the book. And so, when I received an invitation from Kelly Whitmer in late 2022 to contribute to a forum entitled “Knowledge and Power: Projecting the Modern World,” I was thrilled to return to a facet of the Panatomic Canal which the book had only hinted at: how the work to determine where to build the new waterway relied upon and affected Indigenous people and their environment in eastern Panama.

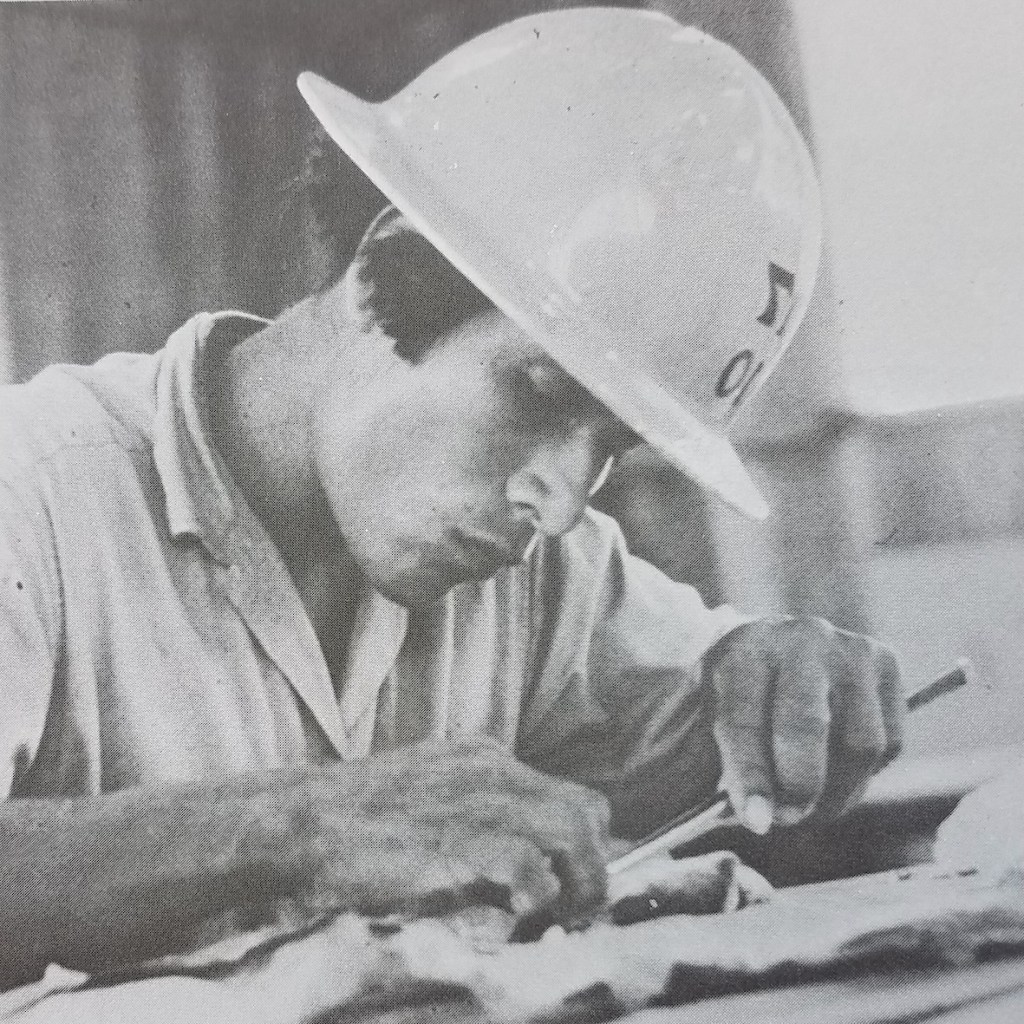

I had previously encountered images of Indigenous workers and residents published by the Atlantic Pacific Interoceanic Canal Study Commission (CSC), a key set of actors in the book. Despite the inclusion of a few such tantalizing photos, the CSC files contained little of substance regarding the Indigenous communities living along the proposed canal routes. I gained a much more thorough picture of the contributions of Indigenous people to the canal feasibility studies from a different archival collection, thanks to historian Roger Turner.6 His research into the Air Resources Laboratory, Weather Bureau, and other US governmental agencies involved in Panatomic Canal contracts led him to create a super-helpful finding guide, which he generously shared with me.

An image of a Guna worker included in the Fourth Annual Report of the Atlantic-Pacific Interoceanic Canal Study Commission (31 July 1968), with the caption, “More than 60,000 animals were collected to study reservoirs and vectors of human disease along the Colombian route. Above, a Cuna Indian dissects a rodent.” Image: United States National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland (public domain).

An image of a Guna artisan included in the Fourth Annual Report of the Atlantic-Pacific Interoceanic Canal Study Commission (31 July 1968) with the caption, “Human ecology studies included population, dietary and cultural information on the natives. Above, Cuna Indians on San Blas Islands, Panama.” Image: United States National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland (public domain).

A final fortuitous insight came during the pandemic years of 2020-21, when US and European biologists were no longer able to visit their tropical research sites. This disruption sparked conversations about the history of scientists from wealthy nations conducting short-term projects in the Global South, who often failed to acknowledge the essential contributions of local informants and researchers. In such reckonings with “parachute science,” I saw a direct link back to the ways in which US workers relied upon Indigenous people to investigate proposed routes for the Panatomic Canal, as I detail in my article.

My article is the only one in the special issue not set during the Early Modern era, and at first I felt awkward about this. However, being part of the issue wound up providing another serendipitous opportunity to consider my topic in new ways. Interacting with the wonderful scholars involved in the special issue helped me clarify some of the enduring but unjust continuities linking colonial and high modernist projects, both built and unbuilt.

The process of generating knowledge about the natural world—what we typically call “science”—always involves collective work. So too does the field of history. I look forward to continuing this conversation with other historians of knowledge, and thinking further about how we can contribute to both the historiography of unrealized projects, as well as contemporary initiatives to make science more socially and environmentally just.

Christine Keiner is the author of The Oyster Question: Scientists, Watermen, and the Maryland Chesapeake Bay since 1880 (2009) and Deep Cut: Science, Power, and the Unbuilt Interoceanic Canal (2020), and chair of the Department of Science, Technology, and Society at Rochester Institute of Technology.

- Stephen Bocking, Ecologists and Environmental Politics: A History of Contemporary Ecology (Yale University Press, 1997), x. ↩︎

- Christine Keiner, Deep Cut: Science, Power, and the Unbuilt Interoceanic Canal (University of Georgia Press, 2020). ↩︎

- Karin E. Tice, Kuna Crafts, Gender, and the Global Economy (University of Texas Press, 1995). ↩︎

- Philipp Nicolas Lehmann, Infinite Power to Change the World: Hydroelectricity and Engineered Climate Change in the Atlantropa Project, American Historical Review 121 (2016), 99. ↩︎

- Mike Heffernan, Shifting Sands: The Trans-Saharan Railway. In Engineering Earth: The Impacts of Megaengineering Projects, edited by Stanley D. Brunn (Springer, 2011), 618. ↩︎

- Roger Turner, The Weather Scientists Who Can Forecast a National Security Threat. Zócalo (July 12, 2017). ↩︎

You must be logged in to post a comment.