The Devil is in the Details: Fantastic Schemes and the Quiet Champions of Urban Infrastructure

Read Keith Pluymers’ research article “Regulating the City: Streetscaping, Sewers, and the Project of Universal Drainage in Philadelphia” here.

Keith Pluymers

Illinois State University

In the 1790s, Philadelphia was a city in crisis. Multiple waves of yellow fever had ripped through the city, devastating its population and abruptly halting vibrant urban life. Contemporary physicians fiercely debated the causes of the epidemic and tried to determine if the climate or the city’s atmosphere had changed in some new and dangerous way. Each successive outbreak intensified the fear and uncertainty.

The escalating crisis prompted a wide range of proposed solutions. Notably, the architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe put forward a plan to deliver water to Philadelphia that would allow for “washing the streets, and, if possible, of cooling the air of the city.”1 A plan for artificial cooling at this scale may seem ridiculous—some of Latrobe’s contemporaries thought so and attacked him in print. But plans for deliberate, controlled flooding to clean streets and cool air show up in printed treatises and plans from Philadelphia, London, Gibraltar, and New Orleans throughout the eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries.

Rather than dismissing such schemes as quirky footnotes to the Scientific or Industrial Revolutions, my recent JHoK article, and the special issue it belongs to, try to take them seriously. My article took a step back from flashier projects to show that ambitious plans for deliberate flooding at the end of the eighteenth century were in fact built upon decades of work paving the streets, building sewers, and reshaping local waterways to drain the built environment.

W. Birch and Son, “The Water Works, in Centre Square Philadelphia,” in The City of Philadelphia, in the State of Pennsylvania North America; as it appeared in the Year 1800 (Philadelphia, 1800). Image: The Library Company of Philadelphia.

Records of public works projects like street paving may seem mundane in comparison to plans to control urban temperature or flood streets on demand. But when I consulted the detailed official and personal records from the group responsible for paving and draining Philadelphia—the Streets Commissioners—I found evidence for their larger ambitions. The Streets Commissioners came to see flooding and standing water as problems to be solved through connected infrastructure that drew on and replaced pre-existing creeks, rivulets, and streams, rather than as hyperlocal nuisances confined to a single house or street.

To put this vision into action required new ways of observing, recording, presenting, and analyzing how water moved through the city. The records of the Streets Commissioners did more than list where and when a sewer was built or a street was paved—they revealed new patterns of observation and served as tools to enable connective thinking about the city’s infrastructure.

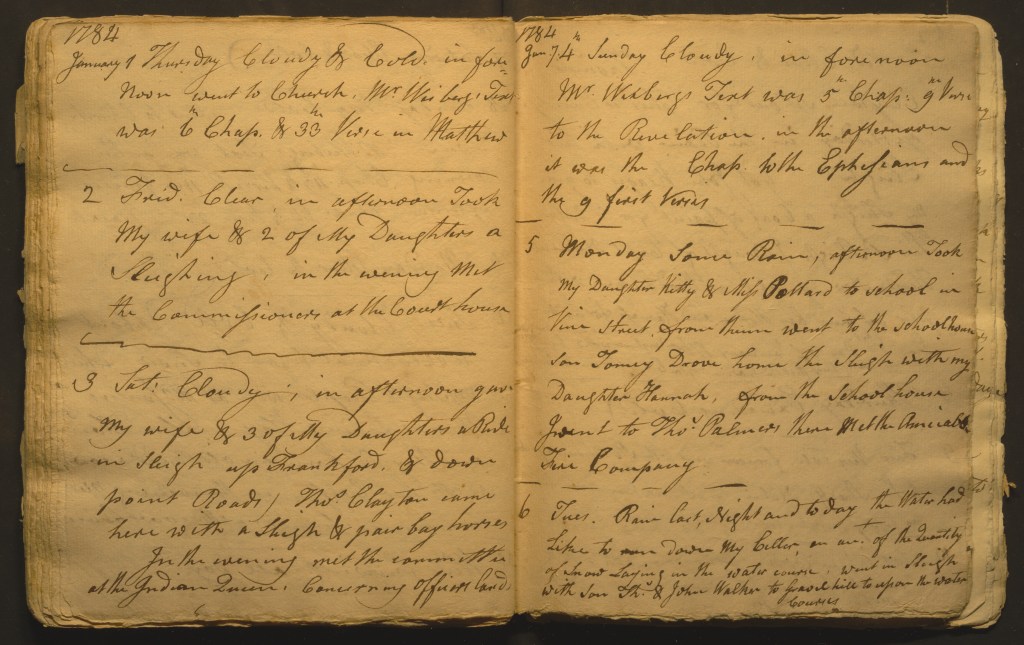

For example, on the night of January 6, 1784, Streets Commissioner Jacob Hiltzheimer reported a late-night sleigh ride with his son and neighbor to inspect how wintry weather affected flows of water across the city. Hiltzheimer’s rides through the city in rain and snow were a regular habit, and he brought the results of these excursions to his fellow Commissioners, which in turn informed their plans for draining the streets.

January 6, 1784 entry from Streets Commissioner Jacob Hiltzheimer’s diary, in which he recorded taking a sleigh ride with his son to inspect the city’s watercourses in the snow. Journal, March 1, 1783 – February 29, 1784, American Philosophical Society, Mss.B.H56d, Vol. 13. Image: American Philosophical Society.

My experience tracking down these records shows just how contingent our knowledge of the past is, even in places with comparatively rich archives, like Philadelphia. I came across a single volume of the Streets Commissioners minutes while I was a research fellow at the Library Company of Philadelphia in the summer of 2021, amidst the uncertainty of the COVID-19 pandemic, tentative institutional reopenings, and efforts to protect the safety of researchers and staff. Online catalogs suggested that a more complete record of the Commissioners’ activities had been preserved at the Philadelphia City Archives, but that turned out not to be the case. The amazing staff at the City Archives did a thorough search through their collections and records to find that the minute books had at some point been transferred to the National Park Service at Independence National Historical Park.

Ultimately, thanks to the combined efforts of staff at three Philadelphia institutions—one private, one municipal, and one federal—I was able to consult the minute books which were so crucial for my article. But the challenge in finding them has meant that other scholars, including those who have worked on Philadelphia’s streets, sewers, and water infrastructure, have not.

These types of records reveal the quotidian details of building and maintaining municipal infrastructure, details which show the ambitions of otherwise minor historical figures and connect their everyday duties with later, more spectacular schemes. Before Latrobe and others proposed their ambitious plans to cool the air or flush cleansing water through Philadelphia’s streets, the Streets Commissioners had already worked to create the intellectual infrastructures required to build a system for the rapid, frictionless movement of water across the city.

As cities around the world grapple with ways to mitigate the effects of our own climate crisis, we will face new challenges, not least learning how to bring the ambitions our moment demands down to the ground.

Keith Pluymers is Associate Professor of History at Illinois State University. His first book, No Wood, No Kingdom: Political Ecology in the English Atlantic was published by the University of Pennsylvania Press in 2021.

- Benjamin Henry Latrobe, View of the Practicability and Means of Supplying the City of Philadelphia with Wholesome Water in a Letter to John Miller, Esquire, from B. Henry Latrobe, Engineer. December 29th, 1798 (Zachariah Poulson, Jr, 1799), 3. ↩︎

You must be logged in to post a comment.