The Strange Decline of the Global Imaginary

Read Björn Lundberg’s research article “Global Knowledge Rituals: United Nations Day and the Global Fifties” here.

Björn Lundberg

Lund University

Annual celebrations of United Nations Day on the 24th of October are excellent examples of the new global imaginary that took root after World War II. Scarred by the horrors of totalitarianism, genocide, and the unfathomable destruction of total war, political leaders and intellectuals turned to visions of a different future: one based not on domination and conquest, but on interdependence, peace, and shared responsibility.

As Manfred B. Steger has shown, the postwar decades witnessed the reinforcement of a certain kind of global consciousness, facilitated by new ideas, technologies, and transnational institutions like the United Nations.1 Across the industrialized world generations of schoolchildren were taught to see themselves not simply as national citizens, but as fortunate members of a broader, often suffering humanity. Global consciousness fused with global conscience, embodying hopes for a better, more equitable world.

Was it naïve? Yes, certainly. Was it self-congratulatory? At times. Did it feature elements of “white saviourism”? Arguably so. Yet, despite these obvious shortcomings, the global imaginary indeed offered a new hope for the future, that extended beyond national frameworks. Today, when populism and new military conflicts are giving rise to a resurgence of nationalism in many European countries, we find ourselves in a state where the somewhat romantic vision of postwar global consciousness appears to be eroding.

So, what happened to the global imaginary, the idea of a united and more equitable world?

In the decades following World War II, the global imaginary was nurtured through education, socialization, and popular culture. Annual celebrations of United Nations Day are one notable example. Often, these events did not merely present the UN and its various agencies, but also included information about global issues that the United Nations sought to address.

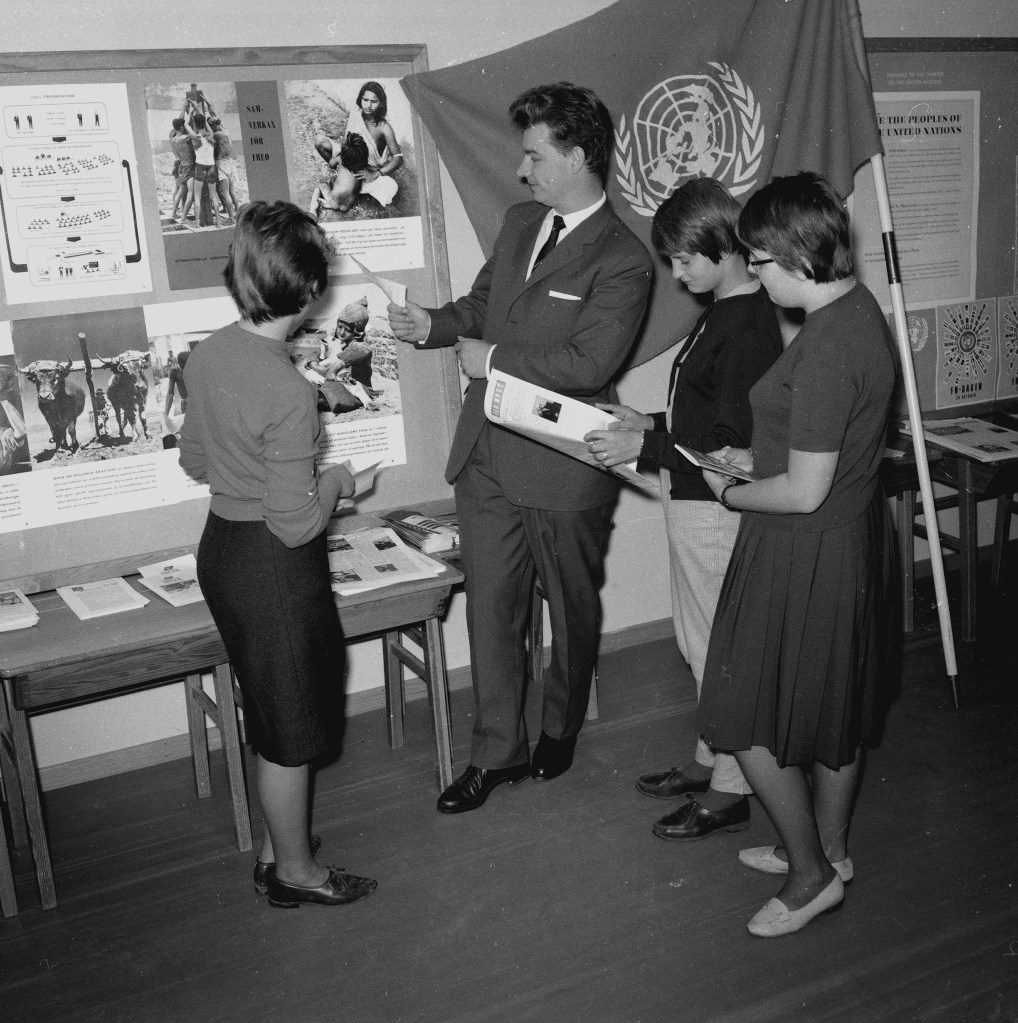

UN Day celebration in Huskvarna, Sweden, highlighting global issues (1960s, exact year unknown).

Photo: AB Conny Rich Foto, Jönköpings läns museum, via DigitaltMuseum (CC-BY-NC).

In my recent JHoK article, I have argued that UN Day celebrations were organized as rituals of global knowledge. Through learning about poverty, health, and other global issues, young people were expected to become more supportive of the UN and its aims, but also to be imbued with a feeling of personal responsibility and willingness to contribute to a better world.

My article charts the evolution of UN Day celebrations in Sweden, where a strong commitment to the United Nations became integral to the national self-image of a neutral small state during the Cold War. Schoolchildren were taught that they were not only citizens of an increasingly affluent national welfare state, but also fortunate members of a wider humanity. In some schools, lessons on global poverty, overpopulation, and inequality were introduced during UN Day or UN Week celebrations, reinforcing the idea that Swedish prosperity carried with it an ethical obligation toward the less fortunate elsewhere.

Global humanitarian campaigns, most notably the national “Sweden Helps” campaigns of 1955 and 1961, which featured the first fundraising attempts for a national Swedish development programme, also included children and young people in schools, and played on the same notions of moral obligation. In this way, global consciousness — awareness of humanity’s interconnectedness — was closely fused with global conscience — a moral responsibility to act on that awareness.

UN Day celebration at Sundsvalls flickskola, Sweden, October 24th 1961.

Photo: Norrlandsbild, Sundsvalls museum, via DigitaltMuseum (CC-BY-NC).

Despite the optimism that marked the early decades of the postwar period, the global imaginary proved vulnerable to new political and economic currents during the final decades of the twentieth century. One was the rise of neoliberalism and its emphasis on individual achievement, market competition, and personal fulfilment over collective responsibility. As neoliberal ideas reshaped societies, the moral underpinnings of global solidarity weakened. In 2011, entrepreneurship was formally introduced into the Swedish school curriculum, and now accompanies key ideals like gender equality and global solidarity among the fundamental values of the curriculum for the compulsory education system.

As a sign of the times, the latest Youth Barometer report – an annual survey of opinions among 17,000 Swedes aged between 15 and 24 – found that young people in Sweden prioritize money over idealism, and self-fulfilment and entrepreneurship over volunteering.

We also appear to be witnessing the return of a more selective form of humanitarianism. Recently, the Swedish government has made a massive reorientation of its development assistance budget, de-prioritizing efforts in Africa and Asia, and instead shifting funding to countries closer to Sweden. In the US, the Trump administration has recently launched a massive attack on USAID, effectively endangering the health of millions in the Global South. The erosion of the global imaginary thus has political consequences. Dreams of a shared world give way to a more fragmented worldview in which solidarity is reserved for the geographically, culturally, or emotionally proximate.

While connecting people across the globe, the explosion of new information technologies has paradoxically contributed to this sense of fragmentation. The collapse of the global imaginary has occurred not despite global interconnectedness, but partly because of it. The increasing dominance of English as a global language and the dominance of American popular culture has contributed to a more homogenized cultural landscape that reduces pluralism. Social media amplifies this dynamic. Although platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram promised global connectivity, their algorithmic structures often prioritize narrowmindedness. Instead of broadening horizons, social media networks provincialize global thinking, feeding users self-confirming, compartmentalized content.

In short, while the architecture of global interconnectedness – technology, trade and travel – has continued to expand, the imaginative framework that once supported visions of a common humanity is now showing signs of erosion. The ideal of a shared world has been challenged by powerful technological and political forces pulling individuals and societies inward, fragmenting global responsibility.

UNICEF Christmas card for the year 1955.

Photo: Antonio Frasconi, via Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Nevertheless, there are still reasons to be optimistic about the future. New forms of global engagement have also emerged, challenging reductionist narratives of decline. Climate activism, global health initiatives, and transnational human rights campaigns offer evidence that the ideal of a shared world has not entirely disappeared. Perhaps most significantly, the adoption of the United Nations’ Agenda 2030 and its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) reflects an ambitious effort to institutionalize global responsibility. Thus, the erosion of the global imaginary is not absolute.

It is definitely not obsolete. As nationalist and individualist currents gain momentum, the need for global solidarity remains urgent. At a time when world leaders are increasingly turning to power politics, and basic human rights are under threat, we must have the courage to imagine something different. The first step towards concrete, peaceful action is to think globally. To imagine a better world, a more peaceful world.

In this case, as so often, history provides us with a useful starting point for envisioning a hopeful future.

Björn Lundberg is Associate Professor of History at Lund University. His research interests include the history of knowledge and the history of childhood and youth. He has published research articles in Media History, The Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth, Contemporary European History, and contributed to several edited volumes.

- Manfred B. Steger, The Rise of the Global Imaginary: Political Ideologies from the French Revolution to the Global War on Terror (Oxford, 2008). ↩︎

You must be logged in to post a comment.