The Biggest, the Most Blank of the World’s Blank Spaces

Read Petter Hellström’s research article “A New New World. Unmapping Africa in the Age of Reason” here.

Petter Hellström

Uppsala University

Joseph Conrad famously described the pull of “the biggest, the most blank” of the world’s blank spaces. But the most remarkable aspect of Africa’s unmapped interior was not its size or its emptiness, but the fact that the region had been mapped before it was unmapped.

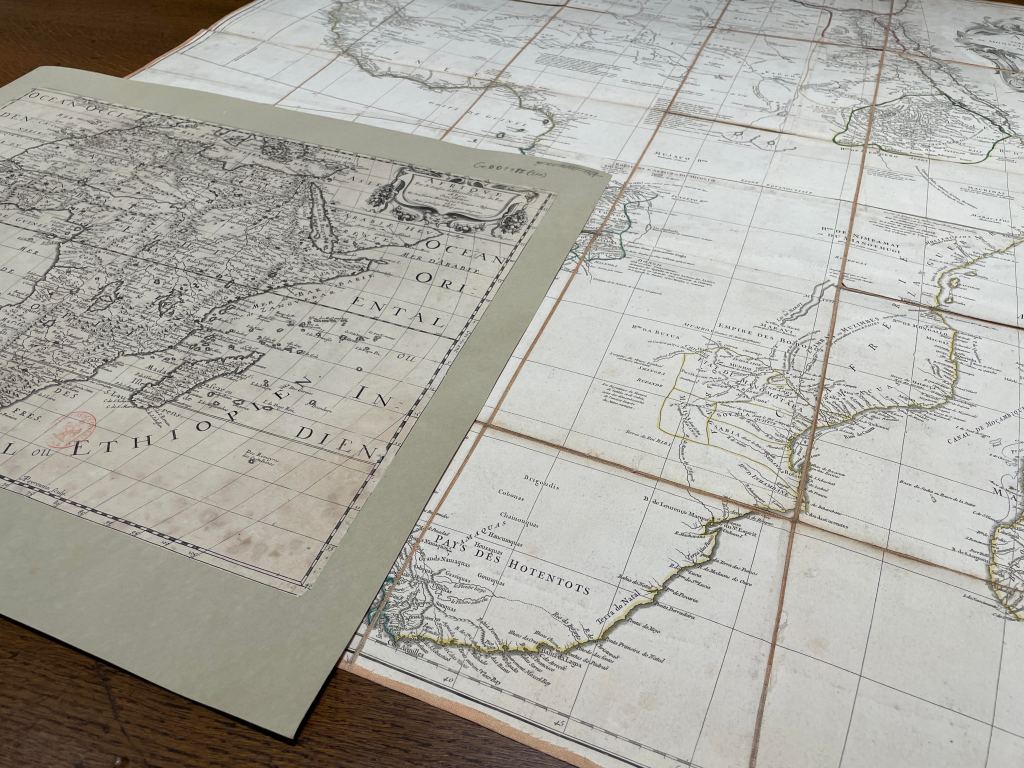

Detail of a coffee table, featuring a copper-plate reproduction of Claes Janszoon Visscher’s 1617 map of the two hemispheres. Photo: Petter Hellström.

When I was a young boy, I had a passion for maps. I would spend hours studying my parents’ atlases, or drawing my own maps of imaginary worlds. Yet no map from my childhood has left a stronger impression than the one on my grandparents’ coffee table. Covered with a relief copper-plate reproduction of Claes Janszoon Visscher’s 1617 map of the two hemispheres, the table stood in my grandparents’ living room between two leather sofas. Made from light wood painted reddish-brown to appear like mahogany, it had clearly been produced to look more antique than it really was. Oblivious of such manipulations, I would trace the outlines of the continents, islands, and rivers with my fingers, as I would recreate the tracing on paper with a pen.

On Visscher’s map, there were not yet any unmapped, blank spaces in Africa’s interior. The blanks only started to appear in the eighteenth century, when geographers in the European Enlightenment began removing topographic features from the map of Africa in favour of blank spaces indicating ignorance or uncertainty. While suppressing a rich tradition of early modern cartography, this reform was soon rationalised as a part of scientific progress.

Once in place, the blank spaces exerted a pull on European minds, especially in the era of high colonialism. Consider the oft-cited opening scene of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899) in which the story’s protagonist, Marlow, describes his childhood fascination with the blank spaces on maps, and especially with “the biggest, the most blank” of all blank spaces:

“Now when I was a little chap I had a passion for maps. I would look for hours at South America, or Africa, or Australia, and lose myself in all the glories of exploration. At that time there were many blank spaces on the earth, and when I saw one that looked particularly inviting on a map (but they all look that) I would put my finger on it and say, When I grow up I will go there. The North Pole was one of these places, I remember. Well, I haven’t been there yet, and shall not try now. The glamour’s off. […] But there was one yet—the biggest, the most blank, so to speak—that I had a hankering after.” (Conrad 1899, 197)

As a number of literary scholars have pointed out before me, Marlow was not alone in experiencing the pull; Conrad had felt it too (see e.g., Hiatt 2002; GoGwilt 1995). In the first part of a series of autobiographical sketches, originally published in 1908, the literary chronicler of European empire recalled that:

“It was in 1868, when ten years old or thereabouts, that while looking at a map of Africa of the time and putting my finger on the blank space then representing the unsolved mystery of the continent, I said to myself with absolute assurance and an amazing audacity which are no longer in my character now: “When I grow up I will go there.” And of course I thought no more about it till after a quarter of a century or so an opportunity offered to go there—as if the sin of childish audacity were to be visited on my mature head. Yes. I did go there: there being the region of Stanley Falls which in ’68 was the blankest of blank spaces on the earth’s figured surface.” (Conrad 1908, 43)

Africa’s blank spaces, which so intrigued Conrad in the lead-up to the Scramble, are unique in the history of cartography. Not because the use of blank spaces to indicate poorly known regions was new at the time, but because there is no other example of a continent or region of the world being unmapped once it had been mapped. As exemplified by my grandparents’ coffee table, which is now standing in my university office, seventeenth-century cartographic representations of Africa were replete with rivers and mountains, kingdoms, and cities. When I first came to realize the sheer scale of cartographic suppression that had occurred at the hands of eighteenth-century geographers, it stirred my curiosity in much the same manner as the outcome had once stirred Conrad’s.

Two maps of Africa, both produced in Paris by royal geographers: Nicolas Sanson’s Afrique, from 1650, and Jean-Baptiste d’Anville’s Afrique, from 1749. Photo: Petter Hellström.

How can we make sense of the fact that unmapped, blank spaces appeared in a previously mapped part of the world? This question was my point of departure in the article “A New New World: Unmapping Africa in the Age of Reason.” In it, I questioned the conventional historiography, which rationalizes the suppression of previously mapped features on European maps of Africa as the natural outcome of scientific progress. Conrad himself reified this long-standing narrative in a popular-historical article for The National Geographic:

“From the middle of the eighteenth century on, the business of map-making had been growing into an honest occupation, registering the hard-won knowledge, but also in a scientific spirit, recording the geographical ignorance of its time. And it was Africa […] that got cleared of the dull, imaginary wonders of the dark ages, which were replaced by exciting spaces of white paper.” (Conrad 1924, 254)

The idea that Africa’s blank spaces were somehow the outcome of improved scientific standards was promoted already in the eighteenth century, and still has some currency in the scholarly literature today. It comes, however, with a number of problems.

The most apparent flaw with the story is, perhaps, that those geographers who left blank spaces on their maps of Africa on the grounds that only certain knowledge should be represented, still registered uncertain, disputed knowledge when they personally judged the sources to be credible enough. As this indicates, the undoing of African cartography had little if anything to do with the period’s technological advances. The geographers who unmapped Africa did not carry out more precise surveys than earlier generations of geographers, for the simple reason that neither seventeenth- nor eighteenth-century geographers visited the continent. Instead, they relied on mediated reports and already available maps, and their ability to judge the trustworthiness of those reports and maps.

Whom would the geographers trust? Whom would they not trust? This question was not without precedents. Blank spaces were not, after all, an innovation of the eighteenth century. Unmapped, blank spaces had been a feature of European colonial cartography ever since the discovery of the New World. What is truly fascinating about the “biggest, the most blank” of all blank spaces is not so much the size or emptiness of Africa’s blank spaces, but their rather sudden appearance in a previously mapped part of the Old World.

Acknowledgment: I thank Djoeke van Netten and Peter van der Krogt for their help in identifying the map on my grandparents’ coffee table.

Petter Hellström is the principal investigator of “Unmapping Africa: Enlightenment Geography and the Making of Blank Spaces.”

Cited works:

Conrad, Joseph. 1899. The Heart of Darkness, part 1. Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine 165: 193–220.

———. 1908. Some Reminiscences, part 1. The English Review 1: 36–51.

———. 1924. Geography and Some Explorers. The National Geographic Magazine 45 (3): 241–274.

GoGwilt, Christopher Lloyd. 1995. The Invention of the West: Joseph Conrad and the Double-Mapping of Europe and Empire. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Hiatt, Alfred. 2002. Blank Spaces on the Earth. The Yale Journal of Criticism 15 (2): 223–250.

You must be logged in to post a comment.